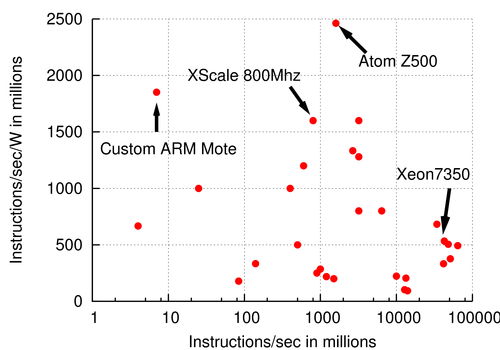

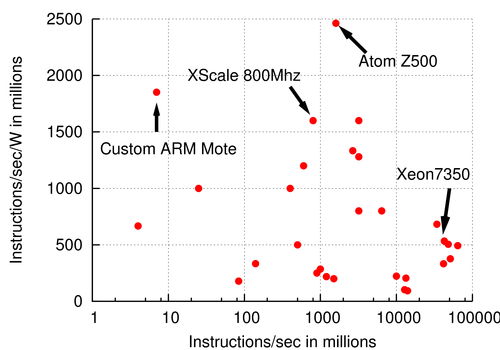

Figure 1: Max speed (MIPS) vs. Instruction efficiency (MIPS/W) in log-log scale. Numbers gathered from publicly-available spec sheets and manufacturer product websites.

FAWNdamentally Power-efficient ClustersVijay Vasudevan, Jason

Franklin, David Andersen

|

Power is becoming an increasingly large financial and scaling burden for computing and society. The costs of running large data centers are becoming dominated by power and cooling to the degree that companies such as Microsoft and Google have built new data centers close to large and cost-efficient hydroelectric power sources [8]. Studies have projected that by 2012, 3-year data center energy costs will be double that of server equipment expenditures [15]. Power consumption and related cooling costs have become a primary design constraint at all levels, limiting the achievable density of data centers and large systems, and pushing processor manufacturers towards alternative architectures. While power constraints have pushed the processor industry toward multi-core architectures, power-efficient alternatives to traditional disk and DRAM-based cluster architectures have been slow to emerge.

As a power-efficient alternative for data-intensive computing, we propose a cluster architecture called a Fast Array of Wimpy Nodes, or FAWN. A FAWN consists of a large number of slower but efficient nodes that each draw only a few watts of power, coupled with low-power storage—our prototype FAWN nodes are built from 500MHz embedded devices with CompactFlash storage that are typically used as wireless routers, Internet gateways, or thin clients.

Through our preliminary evaluation, we demonstrate that a FAWN can be up to six times more efficient than traditional systems with Flash storage in terms of queries per joule for seek-bound applications and between two to eight times more efficient for I/O throughput-bound applications (§3).

Long-lasting, fundamental trends in the scaling of computation and energy suggest that the FAWN approach will become dominant for increasing classes of workloads. First, as we show in §4, slower processors are more efficient: they use fewer joules of energy per instruction than higher speed processors. Second, dynamic power scaling techniques are less effective than reducing a cluster's peak power consumption. We conclude with an analysis of the design space for seek-bound workloads, showing how one should use a FAWN architecture for various dataset sizes and desired query rates (§5).

Data-intensive applications have recently become a focus in the systems research community, with a resurgence in interest on how to store, retrieve, and process massive amounts of data. These data-intensive workloads are often I/O-bound, and can be broadly classified into two forms: seek-bound and scan-bound workloads.

Seek-bound workloads are exemplified by read-mostly workloads with random access patterns for small objects from a large corpus of data. These seek-bound workloads are growing in importance and in popularity with existing and emerging Internet applications. Many of these applications exist in an environment where stringent response time requirements preclude heuristics such as caches or data layout clustering.

The corresponding random seeks generated by these workloads are poorly suited to conventional disk-based architectures where magnetic hard disks limit performance: Access times for a random small block of data on a magnetic disk average 3 to 5 ms, providing only 200-300 requests per second per disk.

Driven by the need to perform millions of random accesses per second [5], social networking and blogging sites such as LiveJournal and Facebook have already been forced to create and maintain large cluster-based memory caches such as memcached [6]. The same challenges are also faced by e-commerce sites such as Amazon, which have catalogs of hundreds of millions or more objects, mostly accessed by a unique object ID [4]. As we show in §5, storing this large amount of data entirely in DRAM is often more costly than storing the data on disk.

The second class of data-intensive workloads we consider is exemplified by large-scale data-analysis. Analysis of large, unstructured datasets is becoming increasingly important in logfile analysis, data-mining, and for large-data applications such as machine learning. Many of these workloads are characterized by very simple computations (e.g., word counts or grep) over the entire dataset. These workloads are, at first glance, well suited to platter-based disks, which provide fast sequential I/O. In many cases, however, the I/O capability provided by a typical drive or small RAID array is insufficient to saturate a modern high-speed, high-power CPU. As a result, performance is limited by the speed at which the storage system can deliver data to the processors.

As one example of scan-bound workloads under-utilizing CPUs, Yahoo won the Terabyte Sort (TeraSort) benchmark in 2008 using a Hadoop cluster with nearly 4000 disks, sorting 1TB of records in 209 seconds [18]. Google subsequently completed the benchmark 3 times faster, using a similar number and type of nodes but with 3 times as many disks [9]. These numbers suggest that much of the speed improvement can be attributed to improving the rate that data can be delivered to the processor from storage, and that the high-speed, high-power CPUs used in the first example were under-utilized.

We propose the Fast Array of Wimpy Nodes (FAWN) architecture, which uses a large number of “wimpy” nodes that act as data storage/retrieval nodes. These nodes use energy-efficient low-power processors combined with low-power storage and a small amount of DRAM.

We have explored two preliminary workloads to understand how a FAWN system can be constructed. The first, FAWN-SEEK, examines exact key-value queries at large scale such as those seen in memcached and Amazon's Dynamo [4]. The second, FAWN-SCAN, examines unstructured text mining queries similar to those expressed in frameworks such as Hadoop and MapReduce.

To understand the feasibility of a FAWN architecture, we evaluated several candidate node systems in their ability to satisfy random key-value lookups and simple scan processing.

| System / Storage | QPS | Watts | Queries/sec/Watt |

| Embedded Systems | |||

| Alix3c2 / Sandisk(CF) | 1697 | 4 | 424 |

| Soekris / Sandisk(CF) | 334 | 3.75 | 89 |

| Traditional Systems | |||

| Desktop / Mobi(SSD) | 5800 | 83 | 69.9 |

| MacbookPro / HD | 66 | 29 | 2.3 |

| Desktop / HD | 171 | 87 | 1.96 |

Table 1: Query rates and power costs using different machine configurations. Power measured using a WattsUp meter (https://wattsupmeters.com).

FAWN-SEEK Performance: Table 1 shows the rate at which these nodes could service requests for random keys from an on-disk dataset, via the network. The best embedded system (Alix3c2) using CompactFlash (CF) storage was six times more power-efficient (in queries/joule) than even the low-power desktop node with a modern SATA-based Flash device.

FAWN-SCAN Performance: We have performed two preliminary studies of scan-bound workloads. First, we look at the distributed sort benchmark provided by the Hadoop framework. Sorting 1 GB of data on one Alix3c2 node took 160 seconds while consuming only 4 W, providing a sort efficiency of 1.6MB per joule. In contrast, a traditional desktop machine with magnetic disk required only 53 seconds but consumed 130 W, a sort efficiency of 0.2MB per joule—eight times less efficient.

Next, we examine a workload derived from a machine learning application that takes a massive-data approach to semi-supervised, automated learning of word classification. The problem reduces to counting the number of times each phrase, from a set of thousands to millions of phrases, occurs in a massive corpus of sentences extracted from the Web. Our results are promising but challenging. FAWN converts a formerly I/O-bound problem into a CPU-bound problem, which requires great algorithmic and implementation attention to work well. The Alix3c2 wimpies can grep for a single pattern at 25MB/sec, close to the maximum rate the CF can provide. However, searching for thousands or millions of phrases with the naive Aho-Corasick algorithm in grep becomes memory-bound (and exceeds the capacity of the wimpy nodes, with unpleasant results).

We have optimized this search using a rolling hash function and large bloom filter to provide a one-sided error grep (false positive but no false negatives) that achieves roughly twice the power efficiency (bytes per second per watt) as a conventional node. However, this efficiency came at the cost of considerable implementation effort. Our experience suggests that efficiently using wimpy nodes for some scan-based workloads will require the development of easy-to-use frameworks that provide common, heavily-optimized data reduction operations (e.g., grep, multi-word grep, etc) as primitives. This represents an exciting avenue of future work: while speeding up hardware is difficult, programmers have long excelled at finding ways to optimize CPU-bound problems.

A FAWN's maximum power consumption is many times lower than a modern DRAM and disk-based cluster while serving identical workloads. Several trends in power and scaling suggest that the FAWN approach will continue to be an energy-efficient approach to building clusters for years to come.

One constant and consternating trend over the last few decades is the increasing gap between CPU performance and I/O bandwidth. The “memory wall” remains a challenge in scaling performance with both CPU frequency and with increasing core counts [13]. For data-intensive computing workloads, storage, network, and memory bandwidth bottlenecks often cause low CPU utilization.

To efficiently run I/O-bound data-intensive, computationally simple applications, FAWN uses wimpy processors selected to reduce I/O-induced idle cycles while maintaining high performance. The reduced processor speed then benefits from a second trend:

Techniques to mask the CPU-memory bottleneck come at the cost of energy efficiency. Branch prediction, speculative execution, and increasing the amount of on-chip caching all require additional processor die area; modern processors dedicate as much as half their die to L2/3 caches [11]. These techniques do not increase the speed of basic computations, but do increase power consumption, making faster CPUs less energy efficient.

A FAWN cluster's slower CPUs dedicate more transistors to basic operations. These CPUs execute significantly more instructions per joule (or instructions/sec per Watt) than their faster counterparts (Figure 1). For example, a Xeon 7350 operates 4 cores at 2.66GHz, consuming about 80W. Assuming optimal pipeline performance (4 operations per cycle), this processor optimistically operates at 530M instructions/joule—if it can issue enough instructions per clock cycle and does not stall or mispredict. A single-core XScale StrongARM processor running at 800MHz consumes 0.5W, providing 1600M instructions per joule. The performance-to-power ratio of the XScale is three times that of the Xeon, and is likely higher given real-world pipeline performance for data-intensive applications. Tellingly, this difference is more severe when considered as I/O operations per joule: the XScale has a 260MHz memory bus; the Xeon has a 1GHz memory bus, five times faster but at 160 times the power.

Figure 1: Max speed (MIPS) vs. Instruction efficiency (MIPS/W) in log-log scale. Numbers gathered from publicly-available spec sheets and manufacturer product websites.

“Energy-proportional” systems attempt to ensure that systems dynamically scale back power usage with decreasing load (e.g., operating at 20% utilization should use 20% of peak power). We argue that reducing peak power is more effective than dynamic power scaling for several reasons.

First, dynamic voltage and frequency scaling (DVFS) benefits for CPUs are now quite limited. A primary energy-saving benefit of DVFS was its ability to reduce voltage as it reduced frequency, but modern CPUs already operate near the voltage floor. Second, transistor leakage currents quickly become a dominant power cost, which drops much more slowly as frequency is reduced [3].

Second, non-processor components have begun to dominate energy consumption in data centers [1], requiring that all components be scaled back with demand, including device controllers and power supplies. Despite improvements to power scaling technology, systems remain most power-efficient when operating at peak power [19]. Given the difficulty of scaling all system components, we must therefore consider “constant factors” for power when calculating a system's instruction efficiency. Figure 2 plots processor efficiency when adding a fixed 0.1W cost for system components such as Ethernet. Because powering 10Mbps Ethernet dwarfs the power consumption of the tiny sensor-type processors that consume only micro-Watts of power, their efficiency drops significantly. The best operating point exists in the middle of the curve, where the fixed costs are amortized while still providing energy-efficiency.

Newer techniques aim for energy proportionality by turning machines off and using VM consolidation, but the practicality of these techniques is still being explored. Many large-scale systems often operate below 50% utilization, but opportunities to go into deep sleep states are few and far between [1], while “wake-up” or VM migration penalties can make these techniques less energy-efficient. Also, VM migration may not apply for some applications, e.g., if datasets are held entirely in DRAM to guarantee fast response times.

Even if techniques for dynamically scaling below peak power were effective, operating below peak power capacity has one more drawback:

Data centers must be provisioned for a system's maximum power draw. This requires investment in infrastructure, including worst-case cooling requirements, provisioning of batteries for backup systems on power failure, and proper gauge power cables. FAWN significantly reduces maximum power draw in comparison to traditional cluster systems that provide equivalent performance, thereby reducing infrastructure cost, reducing the need for massive overprovisioning, and removing one limit to the achievable density of data centers.

Finally, energy proportionality alone is not a panacea: systems ideally should be both proportional and efficient at 100% load. In this paper, we show that there is significant room to improve energy efficiency, and the FAWN approach provides a simple way to do so.

Next, we address when one should use a FAWN or a traditional system by estimating the three-year total cost of ownership for a cluster serving a seek-bound workload.

A cluster needs enough nodes to both hold the entire dataset and to serve a particular query rate. For a dataset of DS gigabytes and a query rate QR, the number of nodes in a cluster is:

|

We define the 3-year total cost of ownership (TCO) for an individual node as the sum of the capital cost and the 3-year power cost at 10 cents per kWh.

If a cluster's TCO grows linearly with the number of nodes, the ratio of dataset size to query rate informs the relative importance between storage size and query rate. For large dataset size to query rate ratios, the number of nodes required is dominated by the storage capacity per node: the important metric is the total cost per GB for an individual node. Conversely, for small datasets with high query rates, the per-node query capacity dictates the number of nodes: the dominant metric is queries per second per dollar. Between these extremes, systems must provide the best tradeoff between per-node storage capacity, query rate, and power cost.

To better understand these tradeoffs, we provide statistics for several candidate systems in Table 2; we choose a cluster composed of traditional nodes (base power of 200W and base cost of $1000) or a FAWN system with wimpy nodes (base power of 5W, $150), pairing each node with several storage solutions. Costs for traditional machines were calculated based on real quotes obtained when building an 80-node traditional cloud computing cluster, and then dividing by a factor of two to account for even larger bulk discounts; costs for FAWN machines were based on private communication with a large manufacturer. These prices exclude the significant costs of power and cooling infrastructure, further biasing against FAWN nodes, which require significantly less power and cooling for a given performance or storage requirement.

Traditional+Disk pairs a single server with five 2TB high-speed disks capable of 300 queries/sec. Each disk consumes 10W. Traditional+SSD uses two Fusion-IO 80GB Flash SSDs, each also consuming about 10W. Traditional+DRAM uses eight 8GB server-quality DRAM modules, each consuming 10W.

FAWN+Disk nodes use one 2TB 7200RPM disk: we assume wimpy nodes have fewer connectors available on the board. FAWN+SSD uses one 32GB Intel SATA Flash SSD, consuming 2W. FAWN+DRAM uses a single 2GB, slower DRAM module, also consuming 2W.

| System | Cost | W | QPS | Queries/Joule | GB/Watt | TCO/GB | TCO/QPS | |||||||

| Traditionals: | ||||||||||||||

| 5-2TB HD | $2K | 250 | 1500 | 6 | 40 | 0.26 | 1.77 | |||||||

| 160GB PCIe SSD | $8K | 220 | 200K | 909 | 0.7 | 53 | 0.04 | |||||||

| 64GB DRAM | $3K | 280 | 1M | 3.5K | 0.2 | 58 | 0.004 | |||||||

| FAWNs: | ||||||||||||||

| 2TB Disk | $350 | 15 | 250 | 16 | 133 | 0.19 | 1.56 | |||||||

| 32GB SSD | $550 | 7 | 35K | 5K | 4.6 | 17.8 | 0.016 | |||||||

| 2GB DRAM | $250 | 7 | 100K | 14K | 0.3 | 134 | 0.003 |

Figure 3 shows which base system has the lowest cost for a particular dataset size and query rate, with dataset sizes between 100GB and 10PB and query rates between 100K and 1 billion per second. The dividing lines represent a boundary across which one system becomes more favorable than another.

For large dataset to query rate ratios, FAWN+Disk provides the lowest TCO because it has the lowest total cost per GB. Intriguingly, if they can be configured with sufficient disks per node (over 50), a traditional system + disks wins for exabyte-sized workloads with low query rates, though this disappears off of our graph (and packing 50 disks per machine may harm reliability).

For small dataset to query rate ratios, FAWN+DRAM costs the fewest dollars per queries/second, keeping in mind that we do not examine workloads that fit entirely in L2 cache on a traditional node. This observation is similar to that made much earlier by the intelligent RAM project, which coupled processors and DRAM to achieve similar benefits [2]. The wimpy nodes can only accept 2GB of DRAM per node, so for larger datasets, a traditional DRAM system provides a high query rate and requires fewer nodes to store the same amount of data (64GB vs 2GB per node). Wimpies designed to address 8GB or more of DRAM would equalize this ratio, making FAWN+DRAM strictly superior to Traditional+DRAM for these random-read workloads.

In the middle range, FAWN+SSDs provide the best balance of storage capacity, query rate, and total cost. As SSD capacity improves, this combination is likely to continue expanding into the range served by FAWN+Disk; as SSD performance improves, so will it reach into DRAM territory. It is conceivable that FAWN+SSD could become the dominant architecture for a wide range of workloads, relegating the other architectures to niches for huge but infrequently-accessed datasets, or tiny datasets with enormous query rates.

Are traditional systems obsolete? We emphasize that this analysis applies only to small, random access workloads. Sequential-read workloads are similar, but the constants depend strongly on the per-byte processing required. Traditional cluster architectures retain a place for CPU-bound workloads, but we do note that architectures such as IBM's BlueGene successfully apply large numbers of low-power, efficient processors to many supercomputing applications [7]—but they augment their wimpy processors with custom floating point units and very low-latency, high-bandwidth interconnects to do so.

The architectural motivation for FAWN borrows from a long line of work on balanced computing [17], multi-microprocessor systems for image processing [12], supercomputing [7], placing smarts near storage [10, 16, 2], and creating arrays of cheap components to leverage “dis-efficiencies” of scale [14]. FAWN takes advantage of a sweet spot in processor efficiency for I/O intensive workloads that do not saturate modern CPUs, greatly reducing both average and maximum power consumption. Given the increasing importance of data-intensive and power-efficient computing, we believe that FAWN is the right approach for losing watts fast.

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers, Charlie Garrod and George Nychis for their valuable feedback and suggestions.